Myth: Elevated ammonia levels are needed for the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis.

Malady: Clinical assessment, and sometimes psychometric testing, are critical for the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy. Ammonia levels have poor diagnostic accuracy and do not seem to change clinical management, in addition to being a notorious logistical nightmare to collect.

The topic at hand is using ammonia for diagnosing hepatic encephalopathy (HE) in patients with cirrhosis and chronic liver disease. This episode I’m coming out swinging. In essence, much of the blog has been about the harms of not questioning common clinical practices that have shaky foundations. This time though, we are going after everyone. Yes, I have quickly pivoted to “we” because of overwhelming cowardice. But WE are going after guidelines this time, ones that brandish sentences that carry a lot of weight without satisfying the burden of proof.

A test that requires specific collection instructions like fasted patients, short torniquet time, minimal fist clenching; a test that needs to be separated, poured into pre-cooled tubes and chauffeured in ice and ran straight away better be worth its weight in gold. As it turns out however, at least in the context it’s most commonly used, the only thing golden about ammonia is the urine it’s found in. Perhaps that’s too reductionist, but by and large, ammonia is not the end-all be-all as it is made out to be for hepatic encephalopathy.

I concede the premise to rely on ammonia in HE, especially in cirrhotic patients, is a tantalising one. Enterocytes and gut bugs generate ammonia that is usually processed by the liver as it enters the portal venous circulation – turned into urea through a series of steps and -ases that we bothered with in medical school – and leaves through the kidney. Muscle and brain also help with this ammonia detox process, to a lesser extent. If you compromise these steps, either in way of reduced hepatocytes or porto-systemic shunting allowing ammonia to bypass these steps, you get hyperannemonemia, however that’s spelt. Ammonia is central in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) whereby the conversion of glutamate to glutamine is obesogenic for astrocytes leading to oedema, oxidative stress and a whole host of badness [1].

So it follows that ammonia is a useful diagnostic tool in overt hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients? Well, not quite. And so our pals – and by pals I mean a one-sided infatuation where the other party does not know you exist – at ChoosingWisely / ThingsWeDoForNoReason [2-3] assert.

This is for a number of great reasons:

- It’s just not a great test: It has middling sensitivity and specificity (75% and 52% respectively in a recent Australian study [4]). For starters, what constitutes a normal ammonia level is quite helpfully variable across laboratories. There are many other reasons for a high ammonia: urea cycle disorders, muscle breakdown, renal disease, GI bleeding, smoking, valproate, Proteus urinary tract infections, and more. Further, we never know the collecting conditions of this fickle test, unless we did it ourselves in which case we know it was definitely not ideal, which further clouds interpretation. These confounds are not minor and negligible either, as this detailed article explores [5].

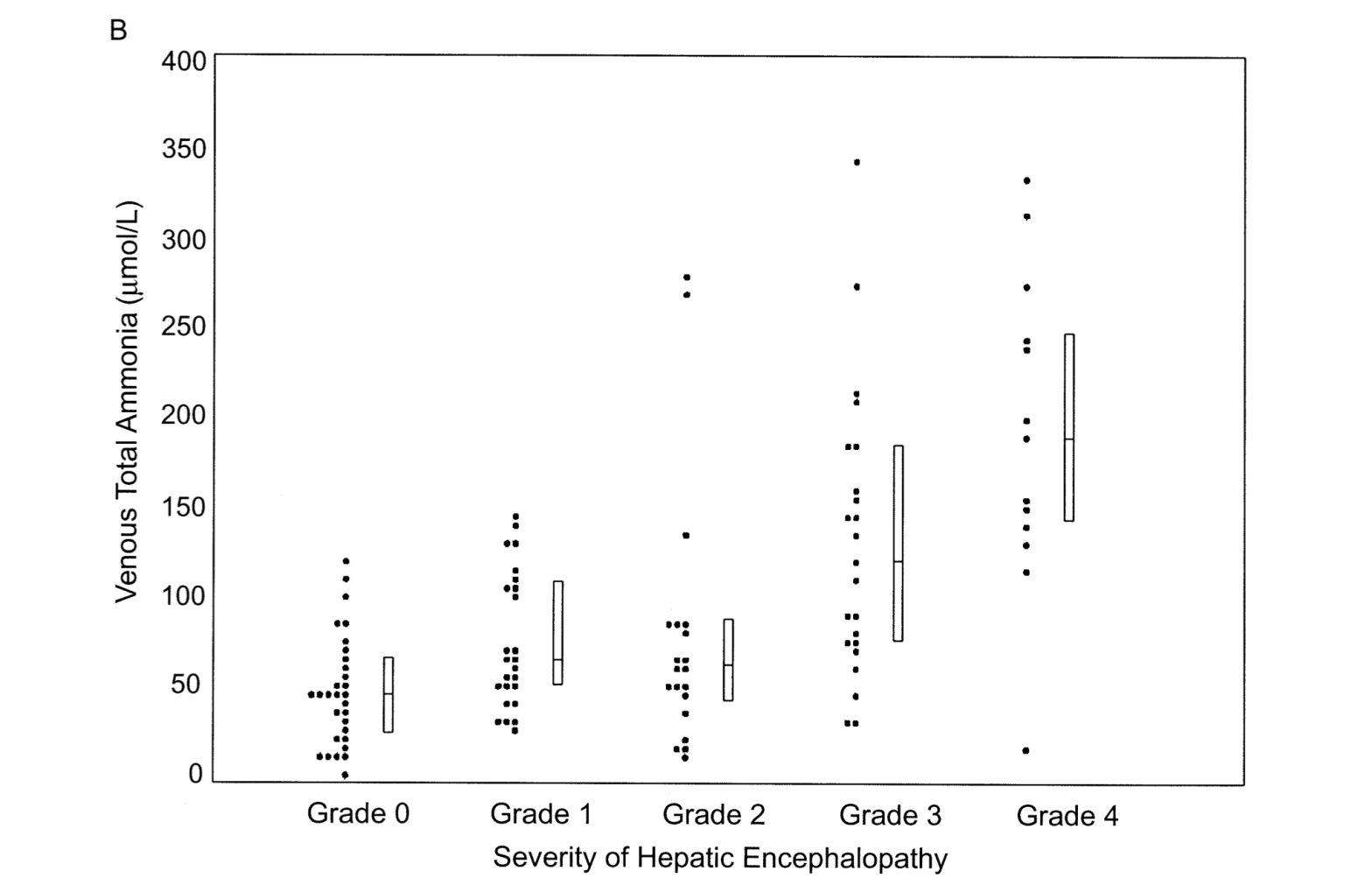

- Levels do not always correlate with degree of encephalopathy: From a highly cited study (716 times at time of writing; Ref 6), this figure is used as proof of a relationship between ammonia levels and hepatic encephalopathy grades. But this figure to me shows that at least half of Grade 0-2 and a good portion of Grade 3 have normal venous ammonia levels (if taken to be defined as < 70, as it is some places). For context, Grade 3 encephalopathy is defined as “gross disorientation” and somewhere between “somnolence to stupor” – Grade 4 is coma. So I am not sure this is making the point that it thinks it is. This is also re-demonstrated in a recent clinical trial aborted due to COVID [7].

- Longitudinal trends are not that informative either: Ammonia need not decrease with time, when there is clinical improvement with treatment for HE – see [8-9].

- A physiological kicker: Lockwood makes the pertinent point that it is not the serum ammonia level but what makes it into the brain that governs HE [10]. Glutamine accumulation in the brain which is seen as the pathogenic end-point actually correlates well with HE grading when measured through magnetic resonance spectroscopy [11].

- High levels may not mean encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: Cirrhotic patients may have high ammonia levels without HE [12]. Correlate clinically.

- Does not change management: The most damning indictment perhaps is that ammonia levels did not change management – which goes back to the crux of why we order any test. [13-14]

Interestingly, this is an area of confusion even amongst expert-led guidance. The 2014 clinical practice guideline that is treated as the definitive document for this has this to say about ammonia in HE – “High blood-ammonia levels alone do not add any diagnostic, staging, or prognostic value in HE patients with CLD”. Great, right? But the sentence following it is “in case an ammonia level is checked in a patient with overt HE and it is normal, the diagnosis of HE is in question”. The French recommendations from 2023 on the diagnosis and management for hepatic encephalopathy assert the same “a normal value casts doubt on the diagnosis of HE” and go a step further to say “ammonia was always elevated in cases of HE” – and these claims are not referenced. A 2020 consensus statement has what I think is a fair statement – a normal ammonia level in an overtly confused patient with cirrhosis should prompt evaluation for causes other than HE. However, this is based on their take that ammonia has a high negative predictive value for HE in cirrhotic patients (i.e. that a negative test is reliable). Once again, none of these three claims have citations.

So here are my receipts instead: Haj et al [14] show that 40% of patients with HE had normal ammonia levels, and in Gundling et al’s study [15] >50% of those with Grade 3 HE had normal ammonia levels (!!). This study [15] shows a disappointing negative predictive value of 48.6%, concurring with the aforementioned Australian study [4] showing a NPV of 65.7% amongst cirrhotic patients. A good negative predictive value, this is not. A good look for guidelines, this absolutely is not either. There was a point I was convinced I was going crazy with these guidelines being so far off base – but thankfully, Deutsch-Link et al [16] had also noticed and my sanity lives on another day. Irrespective, NPVs should rarely be a rationale for a test done to rule in a diagnosis. Colonoscopies in two year olds looking for colon cancer would have a high NPV, it doesn’t mean it is an appropriate test.

The reason I agree with the 2020 statement is not one from evidence. It is common sense to avoid diagnostic fixation, and to always remember Hickam’s Dictum, especially since someone who has advanced pathology such as cirrhosis rarely has that condition in pure isolation. There is a role for ammonia, if you’re looking for one of those funky metabolic disorders, for prognostic assessments and in acute liver failure perhaps. But that’s not what this week’s rant is about.

In the era of data-driven medicine where investigations are king in diagnostics, it is rather quaint – and perhaps confronting – to have a critical diagnosis be based on clinical assessment. Enjoy it.

Giant’s Shoulders:

[3] Great breakdown of evidence in ThingsWeDoForNoReason

[4] Hannah et al in Internal Medicine Journal – interestingly, in this institution ammonia levels were almost uniformly ordered by non-gastroenterologists

[5] American Association for Study of Liver Disease Fellow Series‘ breakdown of the flaws of ammonia; especially helpful for the degree of confounding that collection methods and flaws adds

[9] Nicolao et al‘s detailed work looking at arterial and venous ammonia + partial pressure of ammonia levels in HE

[10] Alan Lockwood‘s physiological explanation of serum ammonia entering the brain as the rate-determining step for HE

[14] One of the largest studies on this topic by Haj et al showing ammonia levels do not change clinical management

[16] Sasha Deutsch-Link and friends speaking some sense in a balanced review of the evidence

Also Cited Above:

[1] Nature Reviews Disease Primers – Hepatic Encephalopathy [generally a great resource, but came across relatively pro-ammonia levels in diagnosis of cirrhotic HE while making concessions about caveats]

[2] Choosing Wisely Canada – Hepatology, Ammonia Levels; offers a brief snippet referencing the 2014 guideline

[6] Ong et al‘s landmark work about ammonia levels and hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis

[7] Subanalysis from a clinical trial for HE ended due to COVID

[8] Clinical trial for HE that relied on HE-scoring algorithm for disease severity, also showed ammonia levels did not correlate with improvement

[11] MR spectroscopy in HE

[12] Kundra et al‘s detailed analysis of ammonia across acute and chronic liver failure

[13] Blinded assessment of ammonia levels’ utility on clinical management

[15] Gundling et al‘s analysis of ammonia’s accuracy in the diagnosis of cirrhosis-related HE in a real world setting

Discover more from Myths & Maladies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.