Myth: A diagnosis is made on the basis of testing.

Malady: Diagnoses are made with the assistance of testing. Tests are not a replacement for clinical judgement, merely an adjunct.

It is the age old conundrum. You ordered a test. It’s come back positive. You weren’t sure if you should’ve done the test in the first place, but you did it anyway. Now what?

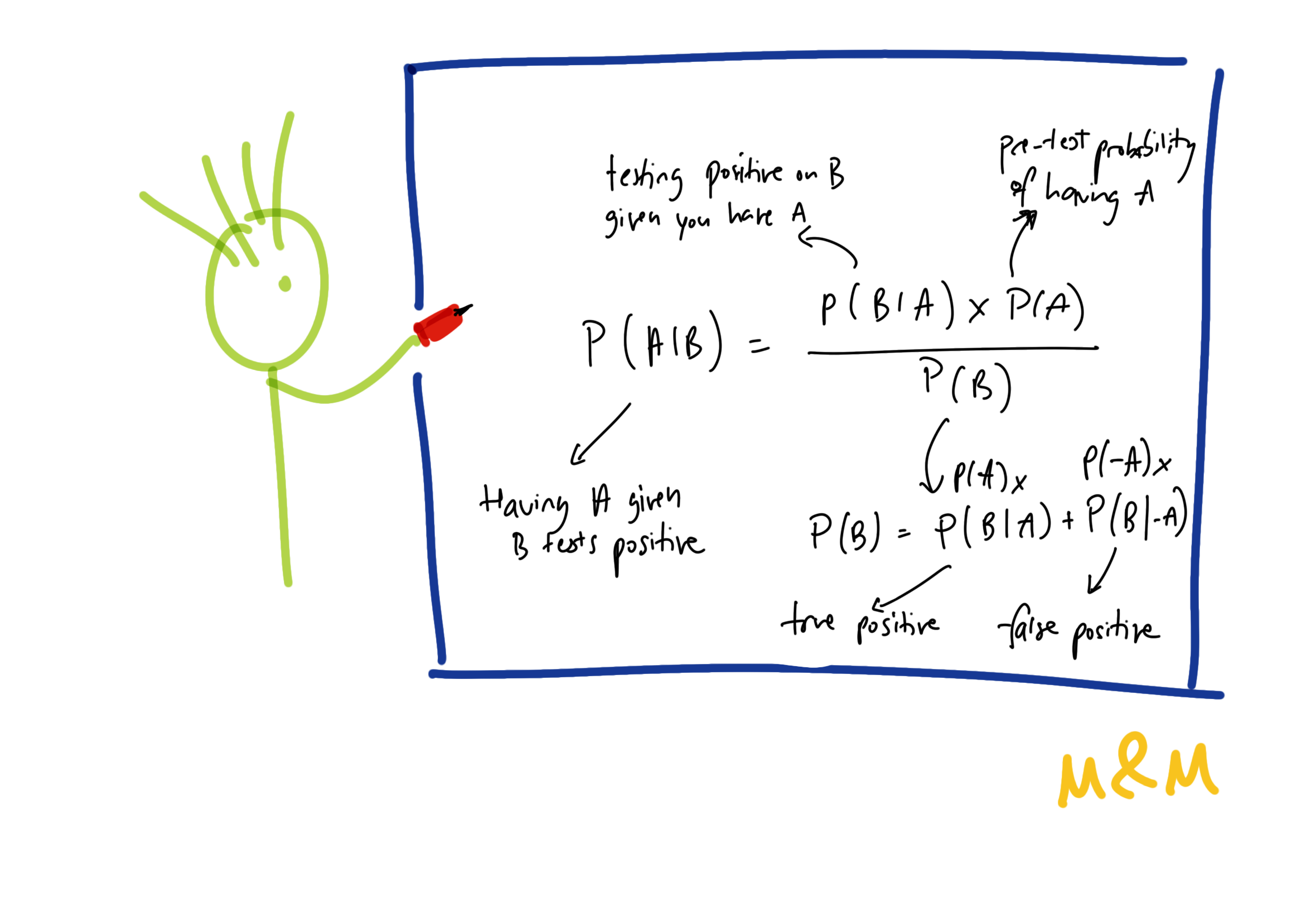

Here is where good old Thomas Bayes comes to help. In the prime of his life, Bayes put forth a formula which we can in fact apply clinically to update the probability of a disease based on new test results. In other words, how much should we trust a test result based on what we know about the patient, and the test.

Apparently I am now our resident mathematician, which is unfortunate because I despise what maths does to my confidence. That aside, welcome to the single most under-appreciated truth in the art of diagnosis. In the time we spent learning about VINDICATE and VITAMIN C and surgical sieves and boring hoofbeats, we should instead have been learning to compute Bayes’ theorem on the go. The travesty is that this is available, albeit hidden away, in our true resident mathematician – MDCalc – under an unassuming ‘Basic Statistics’ calculator. Here’s Bayes’ theorem written out:

Now I don’t want to alienate any of you ex-4 unit maths loving calculus junkies who swore to never do maths again. But bear with me as I take you through a case.

James is a 20 year old gentleman with a virgin abdomen, and no significant medical or family history. He presents with a 1 day history of initially generalised abdominal pain that is now more localised in the right iliac fossa, with onset of nausea this morning. Bloods show a leucocytosis. Because your emergency department has access to a CT scanner, an abdominal examination is not performed.

This recent Cochrane review [1] suggests a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 94% for the diagnosis of appendicitis. These pooled studies show a prevalence of around 45%, which seems a reasonable estimate for a presentation such as above.

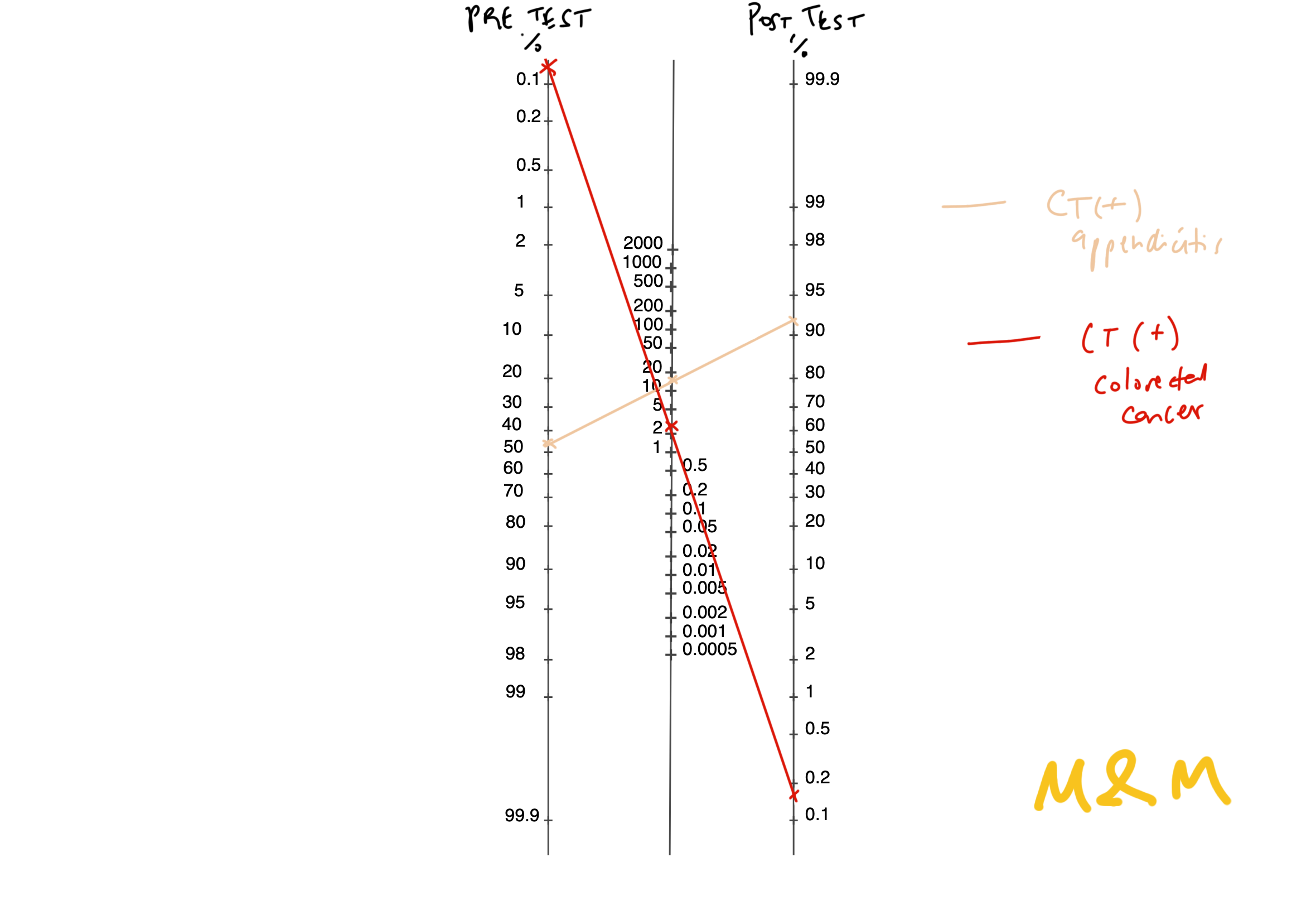

The CT is reported as acute appendicitis. What is their chance of having appendicitis? Well, Bayes’ theorem suggests it is about 93% (i.e. positive predictive value) – which checks out with our intuition, though we are tempted to say 96-100%.

“Incidentally… ”, the CT report also reads, “there is irregularity in the descending colon, concerning for an early malignancy”. Now, what are the chances this patient has colon cancer, a significantly rarer condition in this age group? Pretty high right, at least a double digit percentage, it is clearly identified in the imaging.

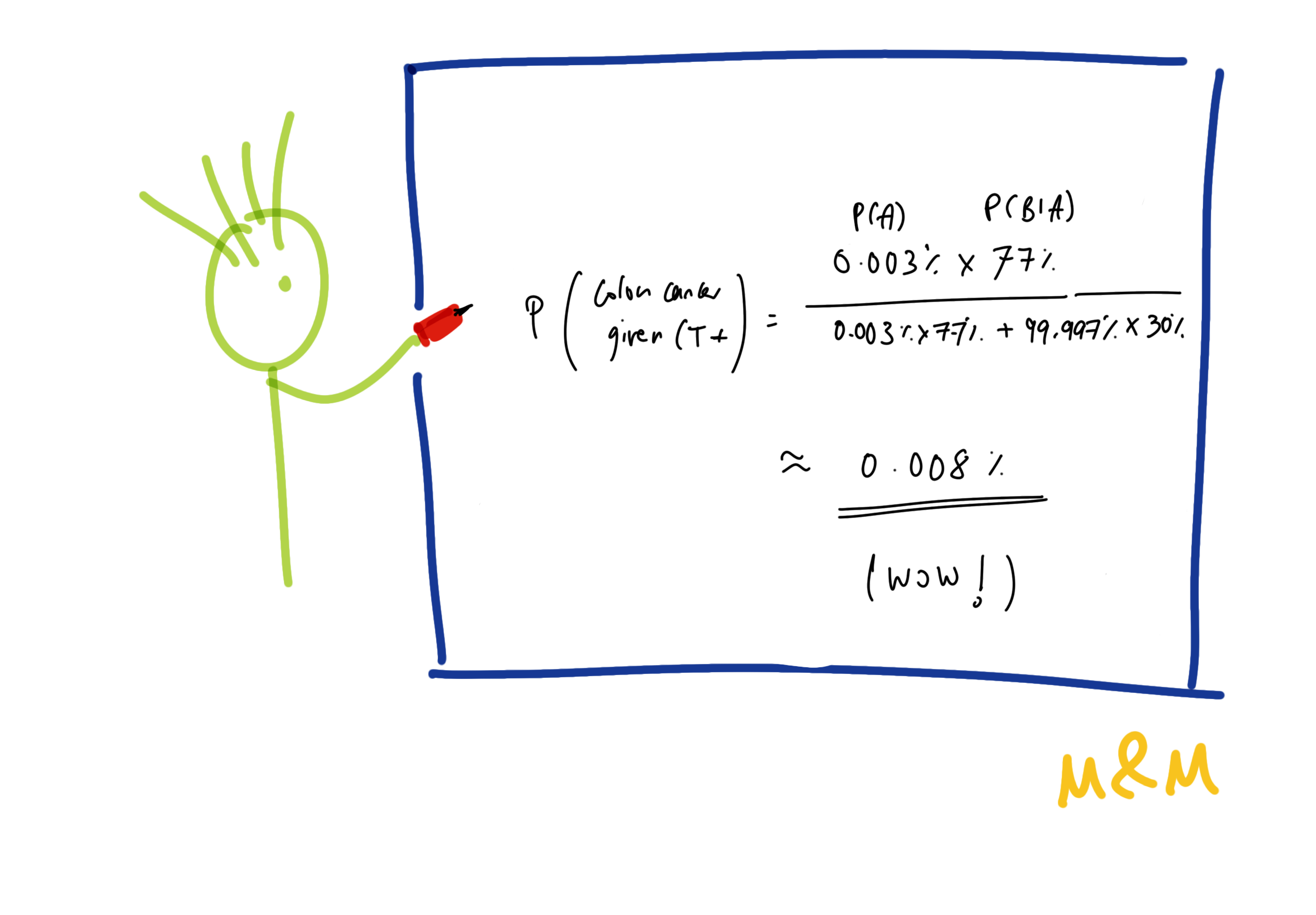

Well, here is where the surprise comes. A recent study estimates the risk of colorectal cancer as around 3 per 100 000 [2] assuming no background risk factors in this age group, a pre-test probability of 0.003%. Radiopedia cites a few studies demonstrating a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 70% in the T-staging of colorectal cancer [3]. Keep in mind, these sensitivity and specificity figures are huge over-estimates in our clinical context – these studies were generally done in patients with known and more advanced stages of colon cancer, and a provided history that is longer than “abdominal pain” prompting a closer look.

Bayes tells us, the actual chance of colon cancer after this positive CT finding is a shocking 0.008%, despite our optimistic over-estimates. That’s it. This paradoxical reality arises from the fact that often, pre-test probabilities are low and tests are quite imperfect. As you can see, this also completely turns clinical practice on its head, because in what world does that patient not get a delayed colonoscopy? In contrast, colonoscopy perforation rates are around 0.7% (10x the colon cancer risk here) [4], and a hatred of bowel prep is closer to 100% as per my anecdotal knowledge.

You can imagine that this is a key complication for most screening tests – the emphasis often tends to be on the sensitivity (i.e. how many of those with the disease will be flagged), while the harms of the false positive rate [FPR] (which is much more commonly encountered since it translates to a larger proportion of overall positives) is minimised.

A useful statistic here is the Likelihood Ratio [LR] (or the Bayes Factor – positive LR = sensitivity / FPR; negative LR = false negative rate / specificity), which has a statistically gorgeous representation in the form of a Fagan nomogram to simplify its use. Do note that we start past the extremes in the nomogram that complicates its use for the second example.

Now, not to forget this works in both ways. If you already start off with a low pre-test probability, then sure, a good test that is negative is quite reliable. But if you’re quite certain about a diagnosis, a negative test merely makes it less likely – but does not rule it out.

So in summary, not to sound like a radiologist, but always clinically correlate. Though the examples above largely focused on diagnostic tests, similar principles apply for physical examination – where the sensitivity and specificity are even more questionable, only magnified by the increased de-skilling across the board. Helpfully, textbooks like Talley’s often report the LR+ of different physical examination findings.

The likelihood ratio I would argue is a much more important, intuitive and clinically relevant measure than sensitivity and specificity. Bayes also serves to highlight that the process of diagnosis is not one of knowing, but one of learning – the more you learn about a patient and update your beliefs and formulation, the closer you are to the truth. The question I leave you with is this – what percentage is good enough?

Giants’ Shoulders:

My dear Veritasium – The Bayesian Trap

This video from 3Blue1Brown also shows a much faster way to compute Bayes on the go – The medical test paradox, and redesigning Bayes’ rule

A readable walkthrough with further information from Drs Webb and Sidebotham – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7808025/

Cited above:

[1] Rud et al‘s Cochrane review on utility of CT in diagnosing acute appendicitis: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009977.pub2/full

[2] Feletto et al‘s study on colorectal cancer incidence in Australia: Trends in Colon and Rectal Cancer Incidence in Australia from 1982 to 2014: Analysis of Data on Over 375,000 Cases

[3] Radiopaedia on Colorectal Cancer: Colorectal cancer | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org

[4] Panteris et al on perforation rates in colonoscopy: Colonoscopy perforation rate, mechanisms and outcome: from diagnostic to therapeutic colonoscopy – PubMed

Discover more from Myths & Maladies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.